The Battle of Midway, fought in June 1942, was an early example of modern carrier warfare, and a dramatic story of brave men facing daunting odds, with an improbable outcome. The U.S. Navy suffered the loss of the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown, the destroyer USS Hammann, 144 aircraft, and over 300 lives. However, the Japanese invasion of Midway Island was repulsed, and the Japanese march across the Pacific stifled. Four Japanese aircraft carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Hiryū, and Sōryū were sunk, the heart of Kidō Butai, the strike force of the First Air Fleet, the single most powerful concentration of naval aviation in the world. The heavy cruiser Mikuma was also lost, along with over 250 aircraft and as many as 3,000 lives. Almost everyone agrees that Midway was the turning point of the war in the Pacific, ranking in that regard with the epic battles of Stalingrad in Europe, and El Alamein in Africa. In each case, the uninterrupted advance of the Axis war machine was halted, and the years-long bloody struggle to final Allied victory began.

The Battle of Midway, fought in June 1942, was an early example of modern carrier warfare, and a dramatic story of brave men facing daunting odds, with an improbable outcome. The U.S. Navy suffered the loss of the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown, the destroyer USS Hammann, 144 aircraft, and over 300 lives. However, the Japanese invasion of Midway Island was repulsed, and the Japanese march across the Pacific stifled. Four Japanese aircraft carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Hiryū, and Sōryū were sunk, the heart of Kidō Butai, the strike force of the First Air Fleet, the single most powerful concentration of naval aviation in the world. The heavy cruiser Mikuma was also lost, along with over 250 aircraft and as many as 3,000 lives. Almost everyone agrees that Midway was the turning point of the war in the Pacific, ranking in that regard with the epic battles of Stalingrad in Europe, and El Alamein in Africa. In each case, the uninterrupted advance of the Axis war machine was halted, and the years-long bloody struggle to final Allied victory began.

In early 1997, Nauticos began discussions with the late Carey Ingram of the Naval Oceanographic Office (NAVO) about working together to search for the great ships sunk at the Battle of Midway and to commemorate the brave sailors and airmen who fought there. In February, 1998, a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement was signed between the Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command, the University of Southern Mississippi, and Nauticos, a collaboration of science, industry, and government. The program promised to bear fruit in areas of deep-sea research, technology demonstration, commemoration of naval heritage, training, education, and business.

As our team was mobilizing, Dr. Robert Ballard announced the discovery of the wreck of USS Yorktown in May, 1998. The following spring, the Nauticos and NAVO team worked to mount an expedition to search for the lost Japanese aircraft carriers. From past experience, including the 1995 discovery of the WW II Japanese submarine I-52, undersea navigation experts at Nauticos knew that the carriers would probably not be found near the reported sinking positions. Researchers and analysts, including Jeff Morris and Jeff Palshook undertook to reconstruct the events of the battle and look for clues to the locations of the lost ships. Central to this effort was the war patrol of the submarine USS Nautilus, which played a key role in the battle and observed the carrier Kaga shortly before it was scuttled. Using a process called Renav, the team reconstructed the Nautilus voyage, calculated an estimated position for Kaga and proposed a search plan to find the wreck.

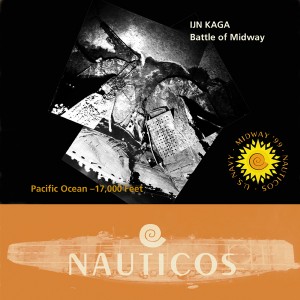

In May, 1999, the group set sail on the research vessel R/V Melville. During this expedition a scattering of debris was imaged with sidescan sonar at over 17,000 feet depth near the computed Renav position. In September, Nauticos and NAVO returned to the site in the vessel USNS Sumner, and captured photographic and video imagery of wreckage suspected to be from Kaga, including a large section of hull that was severely damaged. This wreckage was four miles from the nearest official datum, but only a quarter of a mile from the position Jeff Palshook reconstructed, a great analytical achievement and another proof of the principle of Renav. Unfortunately, only a few days’ time could be spared from Sumner’s other Navy obligations, and the team was forced to leave the site without following the trail of debris to the main hull.

Upon return from the expedition, Nauticos engaged the support of renowned experts in World War II Japanese warship construction and operations, Jon Parshall, Tony Tully and David Dickson with the purpose of analyzing the data and determining which Japanese aircraft carrier had been discovered. Their conclusion was clear: the wreckage was indeed from Kaga.

IJN Carrier Wreckage: Identification Analysis Report

An article based on their IJN Carrier Wreckage: Identification Analysis Report was published in the June 2001 issue of the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings.

December 2000 brought the much anticipated premier airing of The Search for the Japanese Fleet on The Discovery Channel, and on June 4th 2001, the 59th anniversary of the Battle of Midway, David Jourdan of Nauticos was honored to deliver the keynote address at that year’s celebration at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island.

The heart of the Japanese Fleet and many of the aircraft of the brave men who sent it to the bottom remain on the ocean floor, and will be preserved in the cold, dark depths for the next century or longer. We know where they lay, and we will return.

U.S. Navy Commemoration of Midway Day

History of the Battle of Midway

The following are additional website links of interest:

Nauticos Corporation 10/29/99 Press Release:

Navy and Industry Collaborate for Historic Find

Imperial Japanese Navy Page

Jon Parshall’s Website